In the soil just below the hooves of livestock live the Earth’s life support system—as plants decompose, trillions of bacteria, fungi and other soil microorganisms can either turn it into carbon or nitrogen that stays in the soil or into the world’s most powerful greenhouse gases.

While there’s still a lot that scientists don’t know about these tiny creatures, an international research team has been able to affect the way these soil microbes behave, particularly in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Their secret weapon? Grass.

‘Many people disregard soils and see them as a dead entity, but actually soils are alive. We need healthy soils, not just to grow food but also to tackle climate change,’ said Jacobo Arango, environmental microbiologist at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT.

‘We have demonstrated that when some of our improved grasses and legumes are well managed, they are able to help the soil store more carbon meaning fewer greenhouse gases are released into the atmosphere. When cattle are fed a combination of improved grasses and legumes, we’ve also seen a reduction in their methane emissions,’ he said.

Millions of people around the world depend on livestock for their livelihoods. But due to forest clearing for farms and pasture, livestock rumination and manure, agriculture can be a large contributor to national greenhouse gas emissions —ranging from 20% in some countries to 80% in others.

‘Many current livestock production systems are neither profitable nor efficient, occupying much more land area than is necessary, indiscriminately using both soil and water resources and contributing significantly to greenhouse gas emissions,’ said Arango.

One of the keys to improving efficiency of livestock systems is by providing more nutritious grass for livestock to eat.

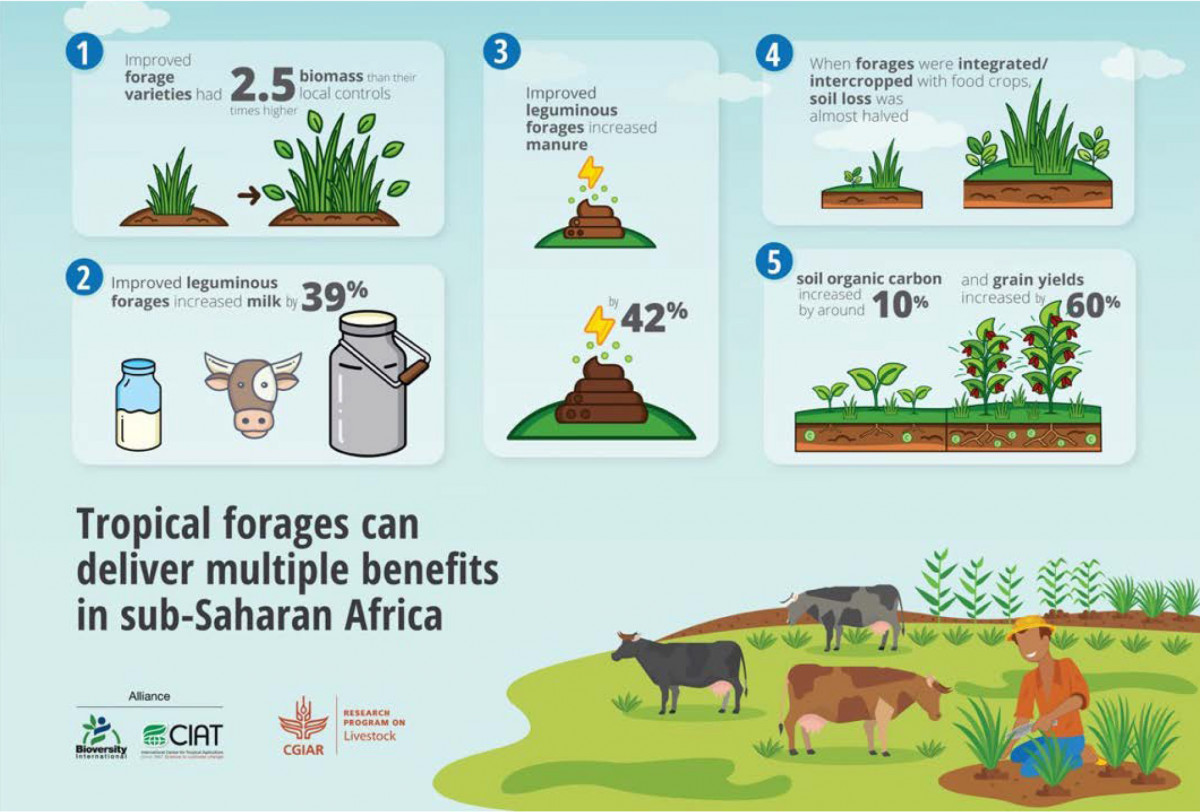

‘If an animal is able to produce more milk or meat from the same area of land because it has access to better forages, then these systems become more profitable because farmers require less feed, which means less land, less water and less greenhouse gas emissions,’ said An Notenbaert, tropical forages coordinator for Africa at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT (Alliance).

Arango, Notenbaert and their colleagues at the Alliance and the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) have been testing a number of improved grass and legume varieties, or forages, in Latin America and eastern Africa to better understand how they affect the environment and determine whether it is possible to feed animals a diet that is low in emissions without compromising production.

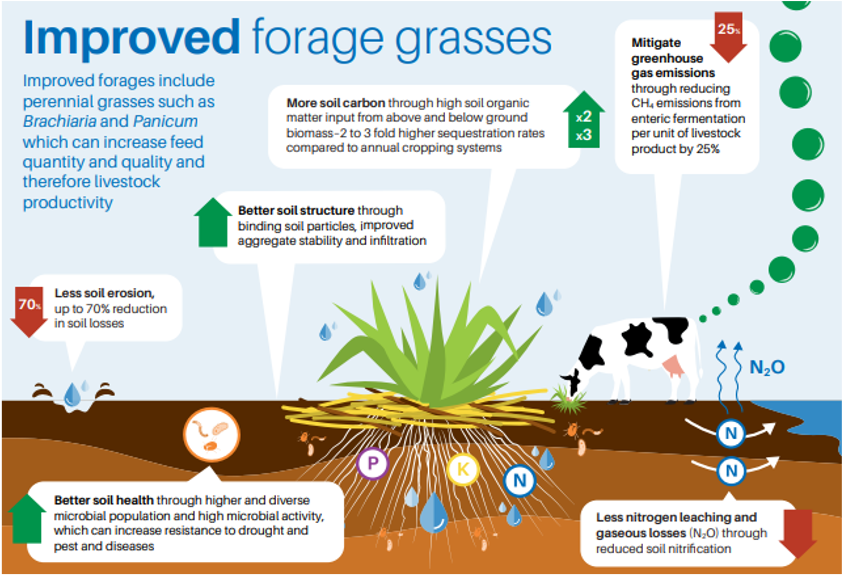

‘We have been focusing on tropical grasses such as Brachiaria and Panicum, because they are the most widely used forages in the tropics, they are adapted to marginal soils and also because a number of varieties that are being developed by plant breeding and selection have high productivity, pest resistance and potential for commercialization,’ Arango said.

Cows in tents

One of the ways livestock contribute to climate change is by emitting methane when they digest, burp and fart. The feed livestock eat greatly impacts how much methane they emit, but relatively little is known about which diets result in the lowest emissions.

To test this, Arango and his colleagues came up with a relatively simple experimental design. They put animals in tents, fed them a specialized forage diet, and then measured the greenhouses gases the animals emitted from that diet.

‘When you are inside a tent, everything that comes out of your body basically stays in that tent. This method allowed us to compare different diets and discover which ones are producing less methane than others,’ Arango said.

Not only did they test different grass diets but they also compared a grass-alone diet with a grass-legume diet to see how it would affect methane emissions. They found that certain varieties of improved forages saw cows emit approximately 10 to 20% less methane.

In many livestock farming systems, manure is seen as a problem—too much of it pollutes the water and the atmosphere and makes animals and people unwell. In the livestock systems where Notenbaert works, manure is seen as a resource.

‘Keeping crop and livestock integrated and interlinked, means you can use the manure to fertilize your crops and therefore you don’t need bring in too many external input like fertilizers and minerals. It’s really about closing the nutrient cycle loop,’ she said.

Building relationships with soil microorganisms

To understand the grass-soil interactions, scientists turned their attention to the Brachiaria root system. What they found was a very deep, extensive root system that dies and grows rapidly.

‘This means that Brachiaria grasses are making the soil healthier but also contributing to soil carbon stocks much more than other types of land uses,’ Arango said.

They also found that certain types of grasses ‘build relationships’ with soil microorganisms, keeping nitrogen in the soil for longer, which increases the chances for the grass itself to uptake nitrogen.

‘Not only does this make for a healthier plant but we’ve also seen 10–30% less nitrous oxide – a greenhouse gas that is 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide—emitted and less nitrogen leaching into and polluting waterways,’ Arango said.

There is great potential for these improved forages to rehabilitate degraded soils, tackle soil erosion and improve the productivity of food crops.

‘Much of our soils are at a point where they have nothing left to give. Nurturing the soils using improved forages will also benefit food crops such as maize or cereals, which can be rotated or intercropped with forages to keep soils healthy. In field trials in Colombia, we’ve seen a 40% increase in grain yields when food crops are integrated with improved forages,’ Arango said.

Reaching carbon neutrality

Arango and his team are now interested in better understanding the genetic make-up of improved forages to know which genes make a plant better in reducing soil nitrification or in interacting with soil microorganisms.

‘If we are able to identify the gene we want, then we could screen a lot of different forage varieties to select the ones that are carrying that gene,’ Arango said.

‘It could halve the time it takes us to understand which forages are best for the environment.’

The aim is not to reduce animal or soil emissions to zero, as that is an impossible task, Arango says, but to help farming systems reach carbon neutrality.

‘It’s about reducing the emissions of livestock as much as possible, reducing the amount of land and water needed to produce the livestock feed and dedicating other parts of a farm to, say, forest restoration, which removes greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. So that, at a farm level, the emissions produced by livestock are offset,’ Arango said.

Deciding which interventions will best reduce agricultural emissions at a system level without compromising productivity is complex. There has also been limited data on the environmental impact of different decisions. To bridge this gap, Notenbaert has been developing a model grounded in IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) methods that helps governments and development agencies assess the environmental impacts of different livestock interventions along the value chain.

‘When most agencies work with farmers they do a cost-benefit analysis of their intervention and make decisions that make economic sense, but they don’t check if these decisions also make environmental sense,’ she said.

‘The model we have developed can assess, for example, what would be the change in land and water requirements of a farm, or a number of farms, if you were to make improvements in feed. Freeing up land or avoiding the conversion of natural lands for feed production could have important biodiversity benefits. The model can also estimate whether this feed improvement would increase or decrease the greenhouse gas emissions.’

The model has been used in Tanzania to assess the environmental impact of productivity-increasing interventions in the dairy value chain in Tanga district. The results show that reduced environmental footprints can be synergistic with productivity increases and increased incomes.

This is important, as many of the farmers the CIAT and ILRI teams work with cannot afford to make very big changes to their farm without also making a profit. Improved forages are a win-win that deliver environmental benefits and also productivity benefits, Arango says.

‘Farmers share the worry about climate change and they want to do something about it. With improved forages, they can see the productivity gains almost immediately so it’s a win-win if they also have environmental benefits,’ he said.

A win-win

Consumers also play an important role in supporting farmers who are trying to follow good environmental practices, Arango said, by purchasing animal products that have met certain environmental standards.

‘We have been working on an environmental certification scheme that helps livestock farmers in Latin America work towards sustainability,’ Arango said.

‘If more consumers were willing to pay a premium price to support farmers who are jumping through the hoops to get their farms environmentally certified, then we’ll see these changes come about quicker. When it comes to climate change, we all need to work together.’

According to Notenbaert the key is making agriculture work with nature, not against it.

‘Livestock has its place because of the nutrition and livelihoods role they play, especially in the developing world where populations are growing rapidly and the demand for meat and milk are rising. As countries look to intensify their production systems, we have to carefully design livestock systems that don’t just consume resources indiscriminately. Forages have an important role to play, particularly in rehabilitating more difficult soils and improving the productivity of marginal lands,’ she said.

--

Learn more:

- Journal article: Improved feeding and forages at a crossroads: Farming systems approaches for sustainable livestock development in East Africa [26 Feb 2020]

- Media: Why feeding cows better grass can help fight climate change ([Deutsche Welle] 24 Feb 2020)

- Paper: Challenges and opportunities for improving eco-efficiency of tropical forage-based systems to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions ([Tropical Grasslands - Forrajes Tropicales] 2013)