When Fatuma Abdullahi’s husband died a few years ago, he left her and their eight children a herd of 50 goats. When she needed money, she would sell an animal.

But in 2017, 40 of her goats perished in a severe drought. Fatuma and her family would have been destitute had she not received a payout of KES 40,000 (US$400) through a government-subsidized insurance program that protects her livestock and those of 18,000 pastoralist households across Kenya.

With the insurance payout, Fatuma bought a female camel. Camels are hardy livestock that can eat most vegetation other animals would avoid and can survive longer without water. Life is still hard, says Fatuma, but the three liters of camel milk she collects and sells daily help cover expenses.

An innovative drought mitigation program

Since 2015, the Kenyan government, with financial and technical support from the World Bank, has been running the Kenya Livestock Insurance Program (KLIP). Based on an index-based livestock insurance program developed by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), KLIP is designed to help protect the food security, assets and livelihoods of the most poor and vulnerable Kenyan pastoralists’ during times of severe drought.

Three seasons after the launch of government insurance program, Kenya experienced one of its worst droughts in half a century, triggering a national emergency from April 2017. A record-breaking total of USD 7 million in indemnity payments were made to 18,000 pastoralist households across eight countries, with some households receiving multiple payments in the year.

The pay-outs ensure that farmers can buy their own food as well as fodder, drugs and water for their livestock during drought seasons. In most cases, the program has enabled beneficiaries to keep their animals alive after the failure of the short and long rains in Kenya in 2016 and 2017.

How it works

The program protects insured pastoralist households against prolonged forage scarcity resulting from severe drought. KLIP provides fully subsidized coverage for an equivalent of 5 Tropical Livestock Units (TLU), equivalent to 5 cattle, or 50 goats/sheep or 1 camel and 4 goats. The insurance program is also available commercially, with households able to purchase coverage through several insurance companies in the eight counties.

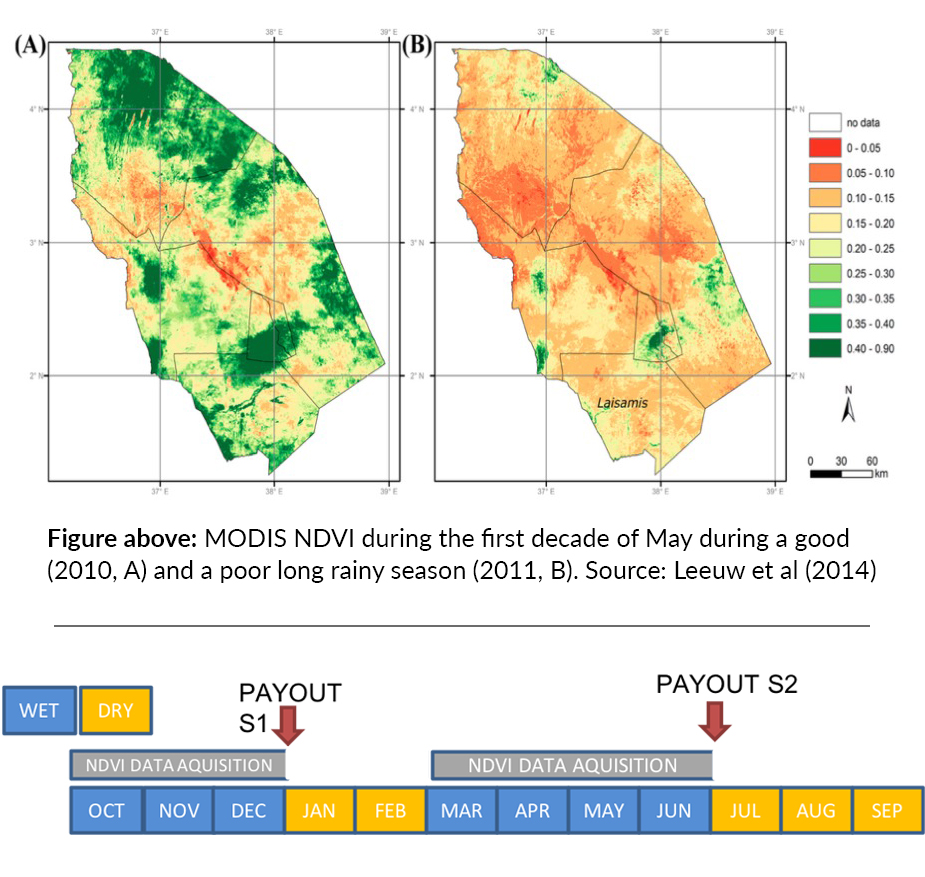

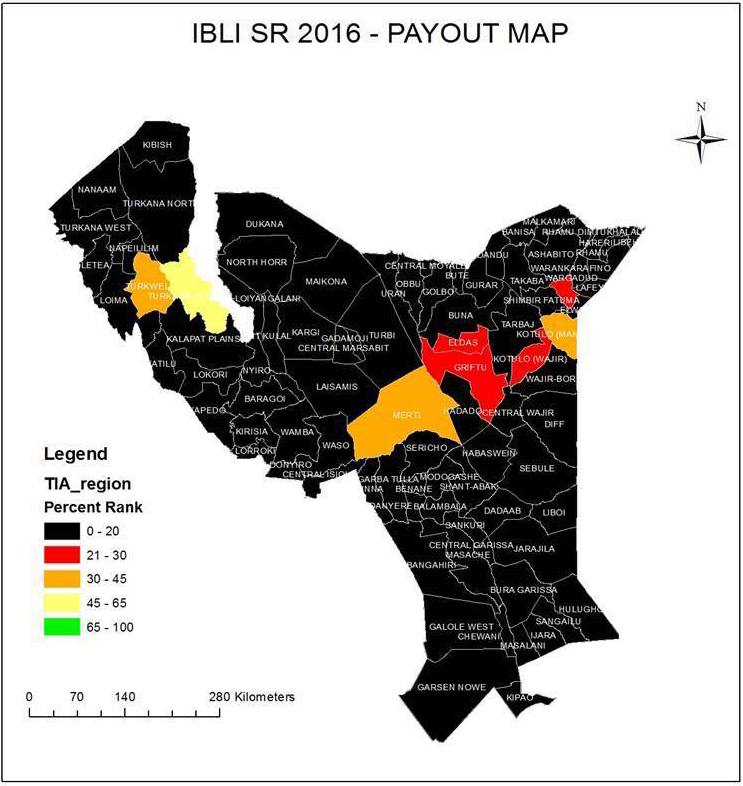

Vegetation is monitored by satellite. Payments for pastoralists are triggered when vegetation conditions indicate that forage has become drastically scarce. Pastoralists receive pay-outs either by cheque or on mobile phones, which can be used to pay for food, water and veterinary services to keep their animals alive or cover essential household expenses such as food, education and debt.

When drought strikes, effects can be devastating

Livestock weaken and die. Household income is severely reduced, often times leading to distress sales of livestock, withdrawal of children from school and fewer daily meals.

Recovery after drought is often difficult, increasing vulnerability to future climate shocks and food security.

Insurance can function as a safety net for pastoralists, to help them protect their livestock and food security during times of severe drought and to improve their chances of recovery.

Takaful Insurance of Africa is the KLIP insurance service provider for Kenya. Abdiaziz Ibrahim Bulle is the company’s county coordinator in Isiolo for the last 5 years, where he has seen steady growth in demand for index-based livestock insurance since it was introduced commercially in 2014. He describes the program as a "hand of help for the poor".

Pastoralists are really feeling the impacts of climate change. Although they do not fully trust this ‘satellite’ that they cannot see, past payments have helped build the reputation and trust in the program.

Abdiaziz Ibrahim Bulle, Takaful

Government role in IBLI

Registering pastoralist households into KLIP consists of manually filling in documents at the community level, which lands on the desks of county officers like Salad Dida Wario, County Desk Officer for KLIP in Isiolo. He inputs the information into a computer and sends the file to colleagues at Nairobi’s Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries.

The beneficiary list ultimately ends up with partner insurance agencies. At pay-out time, a missing or wrong digit in a phone number or misspelled name on a cheque means a beneficiary will not receive their payment claim. At other times, some receive less, while others receive more.

In spite of the challenges, Wario is keen to see the program continue. The initial and current phase of KLIP aims to expose pastoralists like Fatuma to the benefits of index-based insurance through full subsidy of the premiums, so that beneficiaries can gain experiential knowledge about the program.

Government support is also aimed at incentivizing private insurance companies to continue providing pastoralists with insurance and to foster innovation and competition, while yielding greater financial inclusion for pastoralist communities.

The government plans to roll out a partially subsidized KLIP product that will open a window for beneficiaries to be smoothly weaned off the full subsidy. Time will tell how this will be received by pastoralists. When asked whether she would ever pay for livestock insurance out of pocket, Fatuma replies, “No, I’m too poor.”

The Kenya Livestock Insurance Program is a very good initiative for the pastoralists who really need help, but the system needs work - national and county governments need better collaboration.

Salad Dida Wario, County Desk Officer for KLIP in Isiolo

When resources are scarce, conflicts arise

The 2016/2017 drought created a humanitarian crisis in Kenya, affecting about 1.3 million Kenyans. Food security of livestock-owning communities were among the worst hit.

In Laikipia in northern Kenya, headlines were made when desperate pastoralists crossed county border lines with their cattle to illegally graze in private wildlife conservancies. Allegedly fueled by political and historical ethnic tensions, the armed herders attacked several lodge owners and left in their wake dead wildlife and torched buildings.

Most of Kenya is highly vulnerable to drought. Only 20 per cent of the country receives high and regular rainfall. The remaining 80 per cent consists of the arid and semi-arid lands, home to more than half of Kenya’s livestock and about 30 per cent of the country’s 50 million people.

As climate change accelerates and brings on more frequent droughts in the region, the “hand of help” of insurance would be one mechanism to support those most affected by drought.

Expansion plans are under way to cover six additional counties in Kenya and to roll out a partially subsidized KLIP product. In addition, the Government of Ethiopia has expressed commitment to scale up the index based livestock insurance program that was introduced in several parts of the country since 2012.

For more information and blog posts visit ibli.ilri.org/