Hundreds of thousands of livestock farmers across the developing world are seeing substantial increases in livestock’s milk and meat production, thanks to a suite of newly developed grass and legume varieties that are more nutritious, pest and disease resilient.

When managed well, these improved grasses and legumes can not only double the number of animals that a farmer can graze on a piece of land, but also enables them to have locally produced feed to see them through periods of scarcity.

‘When it comes to livestock productivity, there is nothing more important than what animals eat. Even with the significant advancements we are seeing in livestock health and breeding, if we don’t ensure that farmers are able to give their animals high-quality, affordable feed then we won’t see the productivity gains that we all know are possible,’ said Michael Peters, leader of the Tropical Forages Program at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT.

‘These productivity gains we are seeing from the improved forages are being achieved in a sustainable way, with limited need to apply external inputs such as chemical fertilisers or minerals. This results in an ecosystem that has the ability to mitigate climate change, free up land, enhance biodiversity, improve water quality and quantity, enhance soil fertility and potentially halt and reverse land degradation,’ said Peters who also heads the feeds and forages work under the CGIAR Research Program on Livestock.

Small-scale livestock farmers in developing countries face a slew of challenges in simply ensuring their animals are well fed. Shrinking grazing lands in many parts of the world has meant that many farmers aren’t able to let their livestock roam freely. Instead they have to grow or buy animal feed, which often times are of low nutritional quality.

‘That’s why the animals are so low producing in many parts of the developing world - because they just can’t get the nutrients they need from what they’re currently fed,’ said Chris Jones, program leader in feed and forage development at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI).

The right feed can also help address environmental issues

It isn’t just the productivity of the animals that is affected, these challenges come with an environmental cost – not only can overgrazing of small areas of land reduce soil fertility if not carefully managed, but recent studies have shown that undernourished cattle emit more greenhouse gases per unit of livestock product.

‘For example, a cow producing 15 litres of milk and 1.3 greenhouse gas equivalents is much better than a cow producing 3 litres of milk and 1.0 greenhouse equivalent because the greenhouse gases produced per litre of milk is much lower so you need fewer animals for the same level of production,’ said An Notenbaert, tropical forages coordinator for Africa at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT.

Droughts and floods – which are becoming more regular and severe due to climate change – can mean regular feed shortages as well as price hikes, making feed unaffordable for many small-scale farmers.

‘So making sure livestock are well fed is not only important for farmer’s livelihoods, it’s also important for tackling climate change,’ Notenbaert said.

Making grasses more nutritious, productive and resilient

CGIAR scientists have been finding ways to ensure that livestock farmers have access to high-quality, affordable feed for their animals. One of the key approaches has been to improve the grasses and legumes, or forages, that livestock commonly eat by selecting and breeding the plants to be more nutritious, productive and resilient to diseases and extreme weather.

One of the first steps in improving forages was to work out what feed traits were most important to farmers.

‘Farmers are different in different parts of the world – they live in different climates, rear different animal breeds, have different cultural uses for their animals – so what they want from their forages is different. That’s why it’s important to have a menu of forage options for famers to choose from,’ said An Notenbaert, tropical forages coordinator for Africa at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT.

Next, scientists went to the genebanks where they found a number of forages that met the criteria.

One of them was the grass Brachiaria. Native to eastern and southern Africa, Brachiaria first started being bred by scientists in Latin America in the late 1980s, but it took nearly two decades to make the first improved hybrid commercially available to farmers.

‘The breeding process can take a long time, starting from the identification of promising traits in genebanks, re-combining into one outstanding hybrid and then finally, characterizing it and making it available to final users,’ said Valheria Castiblanco, plant breeder with the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT.

In recent years, a new method has emerged that can reduce the amount of time it takes to develop new forage varieties. Scientists at ILRI have been using molecular technologies to better understand how genes control the traits of another popular forage called elephant grass (commonly known as Napier grass).

‘Molecular tools allow us to understand what part of the plant’s DNA is actually controlling the desired traits, whether it be drought resistance or disease tolerance. So instead of waiting three years for a field trial to show which traits are present, plant breeders can more quickly select varieties that are genetically predisposed to being superior,’ said Jones.

Thanks to awareness raising efforts, livestock farmers are increasingly seeing the value of growing forages - Brachiaria is now the most widely grown forage in Latin America, covering an estimated 150 to 200 million hectares. And it will only continue to expand - scientists at CIAT have now developed and released five improved Brachiaria varieties and one blend of multiple Brachiaria cultivars, each with different nutritional, climate, pest and disease resilience properties. Elephant grass has become the most widely grown forage in East Africa and has now had its full genome sequenced, enabling plant breeders to more quickly and easily select better varieties in the future.

These and 170 other forages have been compiled into an online selection and knowledge tool helping farmers to choose which forages will perform best in their climate, soil type, water availability and other factors.

‘Let’s say you select that you want a long term pasture, you’re 500m above sea level and that you have strongly acidic soil of low fertility that drains poorly, you’ll be shown details of a number of forage varieties that you could consider planting,’ said Peters.

Developed by CIAT and ILRI, the tool has been widely used, receiving around 1 million visits per year. It has also recently undergone technical improvement to incorporate language translation.

From genebanks to farmers’ fields

Getting their product to end-users is a major challenge all scientists face. In the case of improved forage varieties, there are many steps required before farmers can access them.

‘Most countries require all plants to be registered. Improved varieties have to go through a process of being tested in different locations, during different seasons to see how they perform. Then paperwork needs to be completed, which is not always straightforward. So not only does it take time but it is an investment and you need somebody who is ready to make that investment,’ said Notenbaert.

To date, forages from the program have been registered and disseminated in more than 70 countries around the globe. Also, researchers have been working with private sector partners and national agricultural research institutes to support the development of national commercial seed production and distribution systems for improved forages within Africa.

“We’ve been testing a number of different Brachiaria grass varieties with 60,000 households from 20 African countries and have seen an increase livestock milk production,” said Sita Ghimire, plant pathologist at ILRI who is now supporting governments across Africa to register these grasses to make them cheaper and more easily available to farmers.

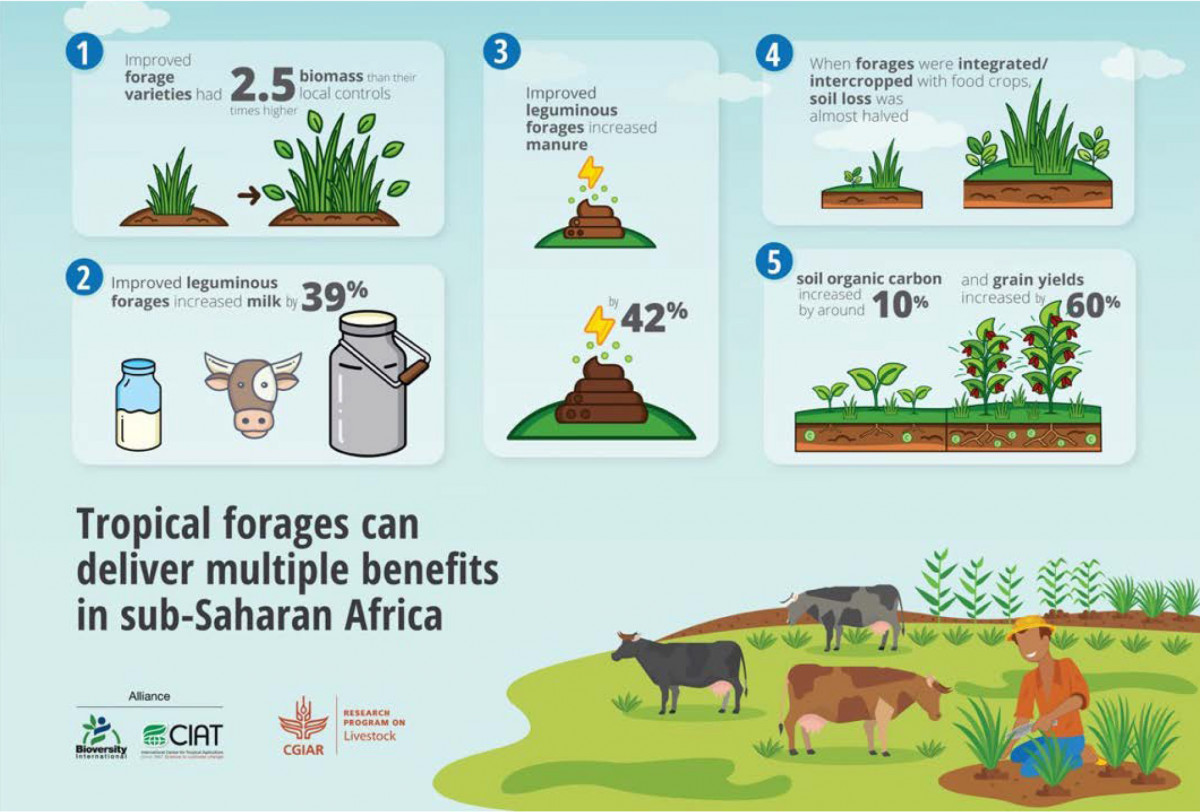

Not only are farmers seeing increased productivity, but the improved forages are benefitting the environment too.

‘We have demonstrated that when some of our improved forages are well managed, they can help the soil store more carbon, meaning less greenhouse gases are released into the atmosphere. When livestock are fed a combination of improved grasses and legumes, we’ve also seen a reduction in their methane emissions,’ said Jacobo Arango, environmental biologist from the Tropical Forages Program at CIAT.

The researchers are currently planning to scale up their work with African farmers, aiming to assist an additional 100,000 farmers across the continent to access improved forage varieties.

‘We are also working on an improved Brachiaria variety that is highly tolerant to a pest in Africa called spider mite,’ said Castiblanco.

The need to improve forages is never ending, said Peters.

‘It is a continuous process. You wouldn’t keep most maize or wheat varieties for 30 years - you would replace them with improved varieties as markets, environmental stresses and agro-ecologies evolve. We need to think about forages in the same way we do crops – that there’s always improvements to be made,’ he said.

--

Learn more